I felt and heard ‘bang, bang, bang’

Published in AIRMail magazine in April 2022.

Forty years on, Jeff Glover has mixed thoughts about the Falklands War. He is glad to have played a part in a winning campaign but for a very long time he felt he had “let the side down”. This was because he was shot down on his very first combat mission, thereby losing one of the six aircraft from his squadron and becoming the only British pilot to be taken as a Prisoner of War during the 1982 conflict.

Jeffrey William Glover, the son of a school headmaster, was born in St Helens, Lancashire, on 2 April 1954. An only child, he was educated at Cowley School, St Helens. Glover gained a BA Honours degree in engineering sciences at St Catherine’s College, Oxford, but was also a member of the University Air Squadron.

From 1976-7, Glover attended the RAF College, Cranwell, in Lincolnshire, where he won the Battle of Britain Trophy for best aerobatics pilot. The following year, at RAF Valley on the island of Anglesey in north Wales, he came top of his course in advanced flying training on Gnat jets. Next, he trained at RAF Leeming in Yorkshire before returning to RAF Valley to be a qualified flying instructor on the Hawk, while also capturing the aerobatics trophy.

Whilst based at RAF Leeming, he met his first wife, Dee, with the couple marrying in February 1981, just 14 months before the start of the Falklands War. In fact, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands on Glover’s 28th birthday. By then, he was serving as a Harrier pilot with No 1 (Fighter) Squadron at RAF Wittering.

In an interview for my new book Falklands War Heroes, Glover recalled that he had been on an intended one-month training course at the German Air Force base Jever on the day that the Falklands were invaded. Two weeks into his course, he was recalled to RAF Wittering as the possibility of war loomed.

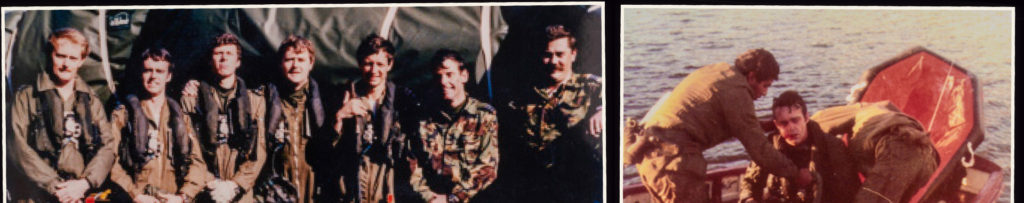

At this point, Glover was serving in the rank of Flight Lieutenant. Eventually, No 1 Squadron deployed nine pilots and six Harrier jets to the South Atlantic.

On the morning of 21 May 1982, Glover took part in his first war-time mission but things did not go to plan. ‘It was the squadron’s second mission of the day. The Wing Commander and I were to get airborne, liaise with HMS Antrim, which was controlling the missions, and await targeting information. We took off at around 8am local time – it was a beautiful day, not a cloud in the sky. I just wanted to perform to the best of my ability, and not let the side down. The Hermes was less than 200 miles to the north-east of the Falklands. I lined up behind the Boss on the carrier. We each had two cluster bomb units and guns loaded. He selected full power and four seconds later I too went to full power, chased him down the flight deck and left the end of the ski jump at 120 knots – nearly 140 mph. I then took 35 degrees of nozzle to be partially wing-borne and jet-borne. We started to climb to around 25,000 feet but the Boss could not retract his under-carriage. He had to abort his mission because of the problem…leaving yours truly on his own to complete the mission.’

Glover was still searching for a target on which to drop his bombs when, flying over West Falkland at more than 500 knots, he was suddenly hit. Glover takes up the story: ‘I felt and heard “bang, bang, bang”. The aircraft then entered a maximum-rate roll to the right – the roll taking no more than a second but it was as if it was happening in slow time. I had three separate thoughts: the first was “I cannot control the roll with this control column”, the second was “that sea is awfully close” and the third was “I have to time my ejection right”. After the aircraft had gone through 320 degrees, I looked down and saw my right hand pull the ejection seat handle. I then heard a metallic bang and I lost consciousness. I woke up about four feet under water, sunny-side up and flapped to the surface and saw the sun again.

‘In fact, I had been hit by a Blowpipe missile that had been fired from the ground by an Argentinian. The missile had hit and taken off half off my right wing which is why I had done a hard roll to the right. The reason I blacked out was that normally you try to pull the ejector handle with both hands but, because it happened so fast, my left hand was still on the throttle so, as I ejected, my left arm went into a whiplash movement at around 600 mph, and I lost consciousness. After I ejected, my parachute opened and I dropped into the freezing sea.

‘So I was in the water in my protective immersion suit and, after what seemed like five minutes of being in shock, I started to think about getting into my self-inflating dinghy which was attached to me by two quick-release clips. At some point, I realised that I couldn’t see out of my left eye – this was because my helmet had flown off during the ejection, which shouldn’t have happened. The end of the oxygen hose, which got separated from my oxygen mask as the helmet flew off, had bashed into my mouth causing some damage. My left side was also completely incapacitated from various injuries. I then heard voices and looked around. There was a little rowing boat with some Argentinian troops in it, holding rifles. In my stupidity, I reached for my RAF-issue pistol but, thankfully, I had mistakenly left it on the Hermes and did not have it with me. The soldiers pulled me out of the water and I was from then on, and for the next fifty days, a PoW.’

Glover’s injuries amounted to a deep cut to his mouth and top lip, severe bruising to the left side of his face, a broken left arm, a broken left shoulder-blade and a broken left collar bone. ‘I was a bit of a mess. I was feeling a bit sorry for myself but I was glad to be alive,’ Glover said with understatement. After his immersion suit was cut off him, he was asked his name, rank and serial number, all of which he provided.

After receiving medical treatment on the Falkland Islands Glover was taken in a Hercules transport plane on 25 May to the Argentine mainland. For a week, his wife did not know whether he was alive or dead but eventually word reached her from the Ministry of Defence that he was alive – but being held captive.

Glover told me that he was never aggressively interrogated or mistreated by the enemy but it was a tough seven weeks with his future uncertain for the whole time, even after the Argentine surrender. After Glover eventually returned home, it was feared he might not fly again. However, he made a good recovery from his physical and mental challenges and returned to flying duties early the next year. ‘It took me seven months before I could fly solo again. It was eventually discovered that I had had a paranoic reaction to isolation and captivity. My problems were more mental than physical,’ he said.

Glover was awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air on 31 December 1985, while still in the rank of Flight Lieutenant. In February 1988, then aged 33 and a father of two young children, he became a member of the world-famous Red Arrows aerobatics team. By then in the rank of Squadron Leader, he said it had been a life-long ambition to fly with the Red Arrows. Glover retired from the RAF in December 1996.

Next, Glover became a commercial pilot, finally retiring in 2019, aged sixty-five. Some six years ago, while working for the Qatari Royal Family, he found himself in Buenos Aries for 12 days and decided to look up the man who had shot him down more than 30 years earlier, Major General (Retired) Sergio Fernandez. ‘We went out for dinner and it was only then that he told me that I had been in the sea, after being shot down, for forty minutes, when I had always thought it was for about five minutes. We had a great evening. He speaks good English and he was, and is, a smashing chap.’

Glover now lives with his second wife, Angela, in Stamford, Lincolnshire. Reflecting on his role in the war nearly four decades ago, he does not see himself as a war hero. However, he added: ‘At the time, as a PoW in 1982, I thought I had let the side down and lost one of our six planes [from his squadron]. But, nearly forty years on, I have got over it.’