HERO OF THE MONTH - MAY 2021

Published in Britain at War in May 2021.

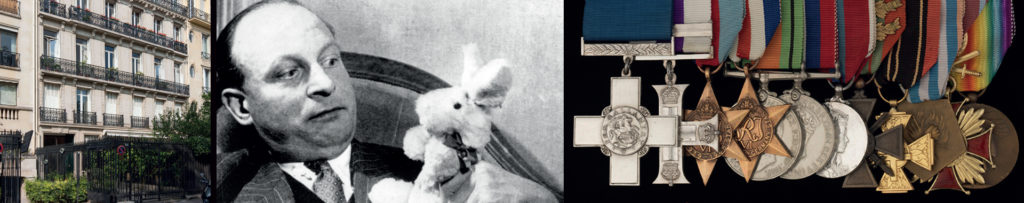

Wing Commander Forest Frederick Edward Yeo-Thomas GC, MC & Bar

Few trained accountants can have spent a life quite as eventful as Forest Yeo-Thomas. Never a man to be chained to his desk, he had more scrapes with death than can be counted, repeatedly thriving on danger and adversity as a secret agent.

Forest Frederick Edward Yeo-Thomas, who was widely known throughout his life simply as “Tommy”, was born in central London, on June 17 1902. His father, John, was a coal merchant, and his mother was Daisy, who went on to have two other sons. Early in Forest’s life, the family relocated to Dieppe, France, where all three boys became bilingual in English and French.

Yeo-Thomas was too young to fight in the British and French armies at the start of the First World War but, by lying about his age, he managed to join the US Army, aged 16, serving as a dispatch rider on the Western Front.

After the war ended and enthusiastic for more frontline action, he took part in the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-20, serving alongside the Poles. Brigadier Sir John “Jackie” Smyth, the VC recipient and author, wrote of Yeo-Thomas: “He campaigned with the Poles against the Russians, was captured by the Bolsheviks and for the first of many times in his turbulent and adventurous life, just escaped being shot.” In fact, Yeo-Thomas escaped from prison by strangling a Soviet guard.

Between the two world wars, Yeo-Thomas flirted with a more conventional career. First, he trained as an engineer with Rolls Royce, before retraining as an accountant for a firm of travel agents and later working in banking. However, he ended up in a senior role with a Paris leading fashion house, Molyneux, while also having a part-share in a gym because of his love of boxing.

Yeo-Thomas had married for the first time in September 1925 and the couple later had two daughters. However, his marriage to Lillian, a Parisian with an English-Danish background, came to an end in 1936, although she refused him a divorce. At the start of the Second World War in September 1939, Yeo-Thomas was still living in France.

Aged 37, Yeo-Thomas attempted to join the British Army but was turned down. He then attempted to join the French Foreign Legion but they were not accepting Britons. He was eventually given permission to join the RAF Volunteer Reserve, working as an interpreter and being evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940.

At this point too, he entered a long-term relationship with another woman, Barbara Dean, a young WAAF, but they could not marry because he had not been divorced.

Yeo-Thomas was frustrated when he was refused any active wartime role, being considered too old. However, following the fall of France in 1940 he was transferred to the RAF Intelligence Branch as an interpreter, and eventually came to the attention of Special Operations Executive (SOE).

In February 1942, he joined the highly-secretive SOE. Rapidly reaching the rank of wing commander, Yeo-Thomas was a fine organiser and coordinator but he was always eager for a more active role. On February 25 1943, he and Andre Dewavrin were parachuted into France to join Pierre Brossolette of the Free French Secret Service.

The next two years were truly eventful and Yep-Thomas was to show the most amazing courage time and time again. His first mission was a success: he enabled a French officer, who was being followed by the Gestapo in Paris, to reach safety and to resume his secret activities in another area.

He also took charge of a US Army Air Corps officer who had been shot down. Because the officer spoke no French, he was in danger of capture but he came back to Britain in the same aircraft that picked up

Yeo-Thomas on April 15 1943, after nearly two months behind enemy lines.

On September 17 1943, Yeo-Thomas, who was known as “the White Rabbit”, returned to France for a second mission. Soon after his arrival, many French patriots were arrested and the situation became tense and dangerous. However, he continued with his clandestine activities.

On no fewer than six occasions, he narrowly avoided arrest himself. On November 15 1943, once again after nearly two months in France, he returned to Britain with intelligence documents obtained from a house the Gestapo had been watching.

In February 1944, Yeo-Thomas was again parachuted into France. However, this time he was betrayed to the Gestapo and seized on March 21. While being taken by car to Gestapo headquarters, he was brutally beaten up.

He then underwent four days of interrogation, interspersed with torture. He suffered regular “immersions”: his head held down, with his arms and legs in chains, in ice-cold water. For the next two months, he underwent regular interrogation and he was told that he would be freed in return for information about the head of a Resistance Secretariat.

Because one of his wrists had been cut by chains, he suffered blood poisoning and nearly lost his left arm. Incredibly, he even made two daring, but unsuccessful, attempts to escape.

His punishment was four months in solitary confinement at Fresnes prison, including three weeks in a darkened cell with little food. The torture continued for all of four months, but he refused to divulge anything of use to his captors.

On July 17 1944, Yeo-Thomas was sent with a party to Compiegne prison, from where he tried to escape twice more. He and 36 other prisoners were then transferred to Buchenwald concentration camp, near Weimar, Germany. En route, they stopped for three days at Saarbrücken where they were kept in a tiny hut and beaten. They arrived at Buchenwald on August 16, where 16 of them were executed and, later, cremated.

On September 14 1944, Yeo-Thomas was convinced that he too was about to be executed and so he penned a letter to his Commanding Officer, Leonard “Dizzy” Dismore. His lengthy letter began: “My dear Dizzy, These are ‘famous last words’ I am afraid, but one has to face death one day or another so I will not moan and get down to brass tacks.”

In fact, he was spared execution and, undaunted, Yeo-Thomas continued to organise resistance within the camp. At this stage, he accepted the opportunity to change his identity with that of a dead French prisoner – but only after a guarantee that others would be given the same opportunity. This switch of identity enabled him to save the lives of two other officers.

The Germans then transferred Yeo-Thomas to a work camp for Jews. He managed to escape from the camp but was picked up nearby. Claiming French nationality, he was transferred to a camp near Marienburg, Poland, for French PoWs.

As the war appeared to be drawing to a close, Yeo-Thomas led an escape by 20 prisoners from the camp in broad daylight. Ten were killed by gunfire from guards and the rest split up into small groups. After three days without food, Yeo-Thomas became separated from his companions. He kept going for another week but was recaptured when he was only 800 yards short of American lines.

Amazingly, he escaped yet again soon afterwards and he then led a party of ten French PoWs through German patrols and a large minefield to reach American lines. He then survived the remainder of the war.

It was not until February 15 1946 that Yeo-Thomas was awarded the GC. His lengthy citation ended: “Wing Commander Yeo-Thomas thus turned his final mission into a success by his determined opposition to the enemy, his strenuous efforts to maintain the morale of his fellow prisoners and his brilliant escape activities. He endured brutal treatment and torture without flinching and showed the most amazing fortitude and devotion to duty throughout his service abroad, during which he was under the constant threat of death.”

Yeo-Thomas was one of just six SOE agents to be awarded the GC after the war. Four of these decorations were awarded posthumously and the only other SOE agent to survive and receive the GC was Odette Sansom.

For his earlier bravery, Yeo-Thomas had been awarded the MC and Bar in March and May 1944 respectively. His other medals and decorations included the Legion d’Honneur and Croix de Guerre and the Polish Cross of Merit.

After the war, Yeo-Thomas returned to live in Paris with his long-term partner, Barbara Dean. Once again he worked for the Molyneux fashion house and he also took up a position with the Federation of British Industries.

After the war too, Yeo-Thomas became an important witness at the Nuremberg War Trials, identifying key German officials who had abused their wartime roles. He was also an important prosecution witness at the Buchenwald Trial held at the former Dachau concentration camp in 1947.

Published in 1952, Bruce Marshall’s biography “The White Rabbit: The Secret Agent the Gestapo could not crack” turned Yeo‐Thomas into a public figure. The author said Yeo-Thomas suffered from “an ordeal of incredible torture and suffering that only a man of indomitable spirit could have endured.”

In 1967, the BBC adapted Marshall’s book for television, with Kenneth More playing the lead in a four‐part series.

Yeo-Thomas’s bravery also intrigued Ian Fleming, the best-selling author, but suggestions that the former SOE man was the main inspiration for the fictitious James Bond character appear wide of the mark. Fleming was, however, aware of Yeo-Thomas’s famous “farewell letter” penned in 1944 and, like many others, greatly admired the agent’s courage.

During his final years, Yeo-Thomas was troubled by ill health, brought on by his many wartime ordeals and his abuse at the hands of the Gestapo. He died in Paris on February 26 1964, aged just 61.

Yeo-Thomas’s ashes were later interred in the Glades of Remembrance at Brookwood cemetery, Surrey. Over the years, there have been many memorials and commemorations in honour of this courageous man.

In 1972, a street in Paris’s 13th arrondissement was renamed Rue Yeo‐Thomas and in 2001 a bust was installed in the Parisian district in which the war hero lived after the war. In 2010, an English Heritage blue plaque was erected outside Yeo‐Thomas’s former London home in Bloomsbury, central London.

Yeo-Thomas’s long-term partner, Barbara, helped the author Mark Seaman to publish a second biography of his life. Called “Bravest of the Brave”, it was published in 1997 and once again it led to his astonishing life being remembered by a wider audience.

Barbara Dean had earlier donated his gallantry and service medals to the Imperial War Museum, London. His medal group is on display at the museum’s Lord Ashcroft Gallery along with medal groups from my own VC and GC collection.