HERO OF THE MONTH – APRIL 2013

Published in Britain at War in April 2013.

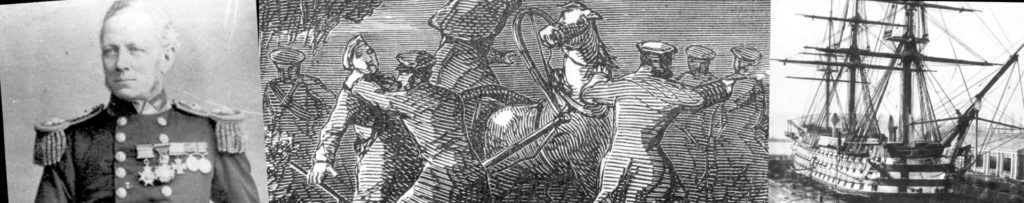

Rear Admiral John Bythesea VC CB CIE

It may surprise many people that there were Special Forces-style operations as long ago as the Crimean War. Most will look upon that conflict as the epitome of conventional warfare, characterised by the tragic and needless loss of life resulting from the Charge of the Light Brigade.

However, the exploits in 1854 that led to Lieutenant John Bythesea, RN, being awarded the VC were no less a Special Forces-style operation than any of the daring adventures of David Sterling and his SAS comrades during the Second World War or by Andy McNab and his team during the First Gulf War.

Early in the Crimean War, the British fleet was stationed in the Baltic off the Russian-held island of Wardo, close to Finland. Captain Hastings Yelverton, from HMS Arrogant, one of the larger ships in the area, paid an official visit to Admiral Sir Charles Napier, the fleet’s commander.

During their meeting, Napier gently reprimanded Yelverton for the fact that vital despatches from the Russian Tsar were being constantly landed on Wardo and forwarded from there to the Commanding Officer of the coastal fortress at Bomarsund. Napier’s gripe was that the British forces had taken no action to prevent this.

Upon returning to his ship, Yelverton mentioned this state of affairs to his junior officers and one of them, Bythesea, immediately determined to do something to disrupt this flow of official mail that British intelligence sources had identified.

Bythesea had been born in Bath, the youngest of five sons of the Reverend George Bythesea, the rector of Freshford, Somerset. He had broken with the family tradition of joining the Army and had instead entered the Royal Navy as a Volunteer First Class. After serving in various ships and gaining promotion, Bythesea was a lieutenant, aged 27, by the outbreak of the Crimean War.

Napier’s conversation with Yelverton about his desire to disrupt the Russian mail took place on August 7 1854. Bythesea applied his mind as to how it might be achieved and came up with an ambitious plan to slip on to Wardo and try to intercept the enemy mail as it was being moved across the island.

Bythesea suggested that a foreign national, Stoker William Johnstone, who he discovered spoke Swedish, should accompany him on the mission. Yelverton’s initial response was that a much larger force should accompany him but – in true Special Forces fashion – it was eventually decided that a larger party was far more likely to attract unwanted attention.

On August 9, just two day after Napier’s conversation with Yelverton, Bythesea and Johnstone rowed ashore on their own, clearly with minimal planning relating to what lay ahead.

Luck was on their side. They made their way to a local farmhouse, where the owner had been forced to hand over all his horses to the Russians and was therefore only too willing to help them.

The farmer not only gave them food and lodgings but also told them how the Russians had improved a nine-mile stretch of local road to made it easier and quicker for messengers to convey the despatches to Bomarsund.

However, the two men had not succeeded in getting ashore unnoticed. Informants had told the Russians that a small shore party from the British fleet was on the island and, as a result, search parties had been sent out to capture them.

Bythesea and Johnstone were able to avoid capture only because the farmer’s daughter had given them old clothes in order to disguise themselves as Finnish peasants.

On August 12, having been on the island for three days, Bythesea was told by the well-informed farmer that the Russian mail boat had landed and the despatches were to be sent down to the fortress at Bomarsund at nightfall, with a military escort to accompany them part of the way.

That night, Bythesea and Johnstone hid in the bushes along the route. They watched from a safe distance as the military escort, reassured that the road ahead was clear, turned back leaving five unarmed messengers to continue on their own.

Bythesea and Johnstone knew instinctively that the moment had come to strike. Armed with just a single flintlock pistol, they ambushed the five men. Two fled into the night, while the other three were captured along with the despatches.

Bythesea and Johnstone returned to the hidden boat in which they had arrived and forced the three men to row out to the Arrogant. Johnstone steered the craft whilst Bythesea held the pistol and ordered their prisoners to row.

On their arrival at the ship, the prisoners were taken on board while the despatches were taken to Admiral Napier and General Baraguay d’Hilliers, the French commander. Napier was thrilled by the actions of the two men, while d’Hilliers admiration for them was said to be “unbounded”.

Bythesea’s reward for the daring and successful mission was to be given the command of the three-gun steam vessel HMS Locust, which was present at the fall of Bomarsund, as well as at the great bombardment of Sveaborg in August 1855. He was promoted to commander on May 10 1856.

Neither Bythesea nor Johnstone expected their bravery to be officially recognised: both modestly considered they had just been doing their duty. However, at Queen Victoria’s behest, the VC was instituted on January 19 1856 for extreme bravery in the face of the enemy. Furthermore, the awards were made retrospective to the beginning of the Crimean War.

The first VC to have been awarded (in chronological terms) was the decoration to Charles Lucas, who as a young officer was serving as a mate in HMS Hecla, for throwing a live shell overboard on June 24 1854.

However, the next action for which the VC was awarded (although in fact they were the 22nd and 23rd to be officially announced in the London Gazette) were to Bythesea and Johnstone. Bythesea’s VC, the result of a recommendation from Napier and D’Hilliers, was gazetted on February 24 1857.

The first investiture, intended for the first 93 recipients of the medal took place in Hyde Park, London on June 26 1857. On that occasion, 62 servicemen received their decorations from the Queen, while the 31 recipients serving overseas received theirs at a later date.

Bythesea was the second man to have his VC pinned on him by the Queen, who remained mounted on her horse, Sunset, while conferring each award. Johnstone was serving overseas and had his VC sent out for presentation aboard his ship.

Bythesea went on to serve at sea around the world, including the operations in China from 1859-60. For his final seagoing command, he was appointed to the battleship HMS Lord Clyde.

However, in March 1872, the Lord Clyde went to the aid of a paddle steamer that had run aground off Malta. In doing so, Lord Clyde also ran aground and had to be towed off by her sister ship, HMS Lord Warden.

This unfortunate episode led to Bythesea and his navigating officer being court martialled with instructions that neither was to be employed at sea again. For Bythesea, it was a sad end to a previously distinguished and totally unblemished naval career.

However, typical of the man, he bounced back from his humiliation. In 1874, the same year that he married aged 47, he took up the post of Consulting Naval Officer to the Indian Government. Further honours followed – he was made a Companion of the Bath (CB) in 1877 and a Companion of the Indian Empire (CIE) the following year. He retired from the active list on August 5 1877, only to be promoted to rear admiral 17 days later.

Bythesea died at his home in South Kensington, London, on May 18 1906, aged 79. He is buried in Bath Abbey cemetery in his home city, while a memorial was erected for him and his brothers at his father’s old church in Freshford.

Incidentally, little is known about Stoker William Johnstone, Bythesea’s fellow VC recipient. At the time of the incident on Waldo, there was a Leading Stoker John Johnstone, who had been born in the German city of Hanover, serving on board the Arrogant. However, the first name is different and there is nothing to suggest that he spoke Swedish.

It is, perhaps, more likely that the recipient of this other VC was one of the foreign nationals that Napier recruited in Stockholm on the way to the Baltic because he felt his crew was too small. If this explanation is correct, Johnstone is probably an anglicized version of Johanssen.

I have had a lifelong interest in bravery, in general, and gallantry medals, in particular. While admiring all courage, I have an especially high opinion of premeditated, or “cold”, courage. I have always thought it takes a special sort of valour to go undercover behind enemy lines, or to be part of a small, elite unit on a hit-and-run mission against a far larger force.

The participant knows that he is putting his life on the line to a far greater extent than most servicemen do. If the mission goes wrong, the serviceman knows, at best, he might be captured and kept a Prisoner of War for months or even years. At worst, he might be seized, tortured, mutilated or even executed.

Bythesea’s VC came up for auction in London in April 2007. By then, I had large collections of both VCs and Special Forces decorations. When I successfully bid for the Bythesea’s VC, it was, for me at least, in many ways the ultimate military decoration for this period. However, my delight was tempered slightly by the fact that Bythesea’s other medals and awards had been stolen some 30 years earlier and never recovered.

As already stated, the man usually credited with receiving the “first VC” – on the basis of his being the earliest act of bravery chosen for the reward – was Charles Lucas (who was awarded it as a mate but ended up as a rear admiral). Rather forgetful towards the end of his long life, he left his medals (including his VC) on a London-Bath train, and they were never found nor ever recovered. Bythesea’s decoration, therefore, as the second-ever VC in chronological terms, is the earliest extant example.